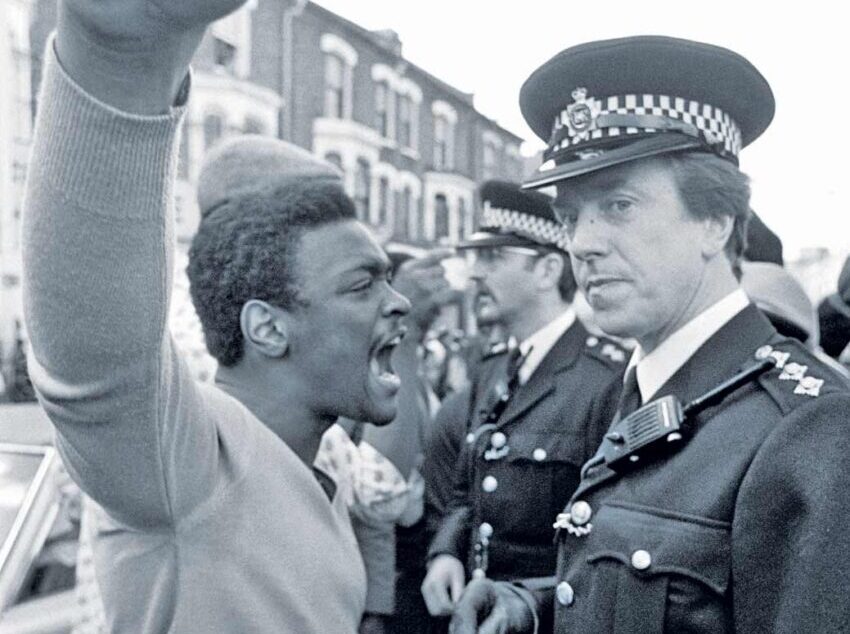

FORTY YEARS ago this month, what was described as one of the ‘worst disturbances’ on mainland Britain for centuries took place in Brixton, south London – in the heart of the capital’s black community. It sent shockwaves across the country that still reverberate today in policing and race relations.

But what difference did it make? In this feature we remember the battle for Brixton. Some call it a riot, some call it an uprising. But 40 years on, the scars of the so-called battle that began on April 10, 1981 and lasted until April 12 are nowhere to be seen.

At least not on the surface. Brixton has been transformed and might be better described as New Brixton. The Brixton that has arisen from the ashes of the burnt out police vans and shops of the clashes.

The ‘battles’ of today are the conflicts that any area of London that’s busy bustling and hustling, thriving and full of street preachers has – who gets the prime spots on the high street, how important the market is to the soul of the place and should developers be allowed to rip the heart out of it?

As for the ‘edge’ in Brixton, it’s still there, but it’s looking like the middle classes will win eventually – if they haven’t already.

At its core Brixton is a village, a suburban one, but a village nonetheless. In the Seventies and Eighties everyone knew everyone. Some people still know everyone. The old timers who still keep their eyes peeled on the road. They’ve seen it all on those streets, they remember April 1981 and what took place, even though the area has transformed almost unimaginably in some respects – ever since Brixton Riot became the name of a local cocktail.

It was a squat city, the People’s Republic of Brixton

Dotun Adebayo

That was back in the late Eighties when the transformation of Brixton really began.

A decade before that, Brixton was a grim place, not only for black people, but in the eyes of authority we were the problem.

Intimidating

The moment you stepped out of the Tube station on to the High Street as a young black man the police clocked you and held their gaze. Intimidating. Daring you. Threatening more so than warning.

But the whole place was grim. It was the urban deprivation that time and the government forgot or had given up on.

Yet Brixton could be such a happy place, despite how tense it was. Then along came a police operation called Swamp ‘81.

Brixton was always an edgy place but after a few days of the area being ‘swamped’ by the police, it was like a razor blade – sharp on both sides. Everybody could see that something was going to give, only the police couldn’t see that they were going to feel it.

Brixton was code for ‘black’, which also become synonymous with rebelliousness, anti-authoritarianism and a sanctuary from the law and order that the police represented – it seemed to write its own rules.

The cops were there in plain sight, but they knew their place. Brixton newsagents sold single ciggies and you could buy a spliff openly on the street corner.

At least on the Railton Road ‘frontline’ you could. The south London enclave also attracted disaffected youth from all over the place – black and white. There was a minor epidemic of young black men getting kicked out of home by their parents at the time and the London postcodes SW9 and SW2 were a cheap and attractive proposition.

It was squat city, the People’s Republic of Brixton, alternative culture. A volatile mix of punks, dreads, Panthers and street preachers dotted its landscape with the intellectual justification for resistance and rebellion.

Strength

Add to that the strength of despondency and anger in the black community across the UK after the death of 13 children in the New Cross Fire just a few months before, the People’s Republic was on edge more than usual.

A tinderbox, not somewhere to lob in a lighted match or any other naked flame – but the cops only went in and lobbed a flame thrower instead. The last thing Brixton needed was Operation Swamp ‘81 and yet someone in high authority, in their wisdom, decided it would be a good idea. A great idea to start picking up young black men and their associates for simply walking. That was what it was like being out and about in the few weeks before it all blew up. Especially up Railton Road from the junction of Atlantic and Coldharbour. The ‘front-

line’ had gone from being a ‘hands-off’ area for the police to being a no-go area for young black men. In the heart of where black people live, people were getting vexed.

It was the topic of conversation from Acre Lane to Loughborough Junction and from Tulse Hill to Stockwell. Brixton was on lockdown even before we ever heard of ‘lockdown’.

Nobody in Brixton had asked for this level of policing

Dotun Adebayo

Since that Thursday evening, the place had been swarming with police, patrolling in threes and fours and fives. Nobody in Brixton had asked for this level of policing. No- body. Nowhere else in Britain had been subjected to this level of policing, not even St Paul’s in Bristol which had erupted in riots the year before in reaction to police behaviour there. On the ghetto grapevine, there was version to version of what was going on and by the afternoon of Friday, April 10, there were a lot of angry people on Brixton High Street as the police got tactic after tactic wrong. This is how the troubles started, as it was reported in brief on the front page of The Guardian on Saturday, April 11, 1981: ‘Three police officers were taken to hospital after a running fight with black youths in Brixton… Scotland Yard say there were eight arrests… after police stopped and questioned a black man wounded in a street fight.’

Refuge

The photo on the back page shows police taking refuge behind a riot shield, the kind we had only ever seen deployed in Northern Ireland during the Troubles there. The battle for Brixton had begun. The Guardian went on to report that up to 60 police officers were involved in a 20 minute-long confrontation. ‘Scotland Yard say that it all began about 6.20pm when two patrolling officers saw a black youth with no shirt and a gaping wound in his back running off. They caught up with him and called an ambulance and proceeded to question him in the back of their car and before they knew it an angry crowd had surrounded their vehicle and some were hurling missiles.

“It was all the result of a misunderstanding,” a police spokesperson said.’ When police reinforcements eventually came they brought riot shields and batons. And then it really kicked off. That night was the relative quiet before the storm of the next day, the Brixton grapevine was buzzing. In and out of the bars nobody had even heard of a Molotov cocktail and yet the streets were humming with the chatter of new faces in town. The streets were full of cars that night, perhaps looking for somewhere else to park. A lot of people seemed to be in the know, a lot of people seemed to be waiting for something to happen.

And so it did. Late on Saturday afternoon. It had been tense all day, especially on the Railton Road frontline which had become a gathering point for hundreds of youths but where the police were determined to keep a high profile. It didn’t take a genius to figure out where it was going to kick off if it was going to kick off.

The arrest of a young black man 100 yards down the road was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Within an hour police were baton charging the crowds around them and were being met with a volley of rubble and having to retreat. This tactic of charge and retreat only served to incense the crowd. Soon their numbers were swelling as more and more people descended into central Brixton in opposition to the police. Some it has to be said only came for the looting, some, it has to be said, came for the burning. ‘The Night Brixton Burned’ was the headline in Sunday morning’s The Observer. ‘Hundreds of black youth joined by some whites rampaged through Brixton last night in a violent explosion of anger.’

More than 50 police and an unknown number of civilians were injured, some seriously, after running battles that lasted several hours. The police’s batons and shields seemed like no match to the bricks and firebombs that rained down on them. Sometimes it looked like the rioters had been training their tactics for months. One hundred and 17 police officers in total and 24 civilians were injured and 101 people were arrested and charged with various offences.

Three ambulancemen also needed treatment. Sunday saw sporadic running battles from about 6pm. The centre of Brixton was sealed off, every now and then there would be a charge by the police followed by a hail of bottles and bricks in return. It went on until late in the evening, but the ‘insurrectionists’ had already been weakened.

The police helicopter that hovered over Brixton all weekend was passing on vital information to snatch squads on the ground who were raiding property across the area and stealthily removing from the scene those they considered to be agitators. They raided Halvin Swaby’s house twice over the two days. Three of his sons had been taken away by officers and kept in police custody in the overflowing cells in Brixton nick.

It was like a war zone. The barricades would not have looked out of place in Belfast.

Dotun Adebayo

On Sunday, April 26, 1981, police officers and 24 civilians were taken to hospital, with 85 arrests made. The then-home secretary William Whitelaw was asked “Why haven’t you been here before?” by locals as he went on a fact-finding walkabout in the debris.

Skinheads

It was like a war zone. The barricades in front of Brixton police station would not have looked out of place in Belfast at the time.

A group of white skinheads who had gathered at the back of the station were soon charged away by the mounted officers behind the barricades. Off Coldharbour Lane white and black looters cleared the entire stock out of a shoe shop as the police stood by and watched them, unsure of the backlash that might accompany an intervention.

By early Monday morning, there was broken glass everywhere and the embers of the ‘uprising’ were dying out. It had still kicked off the preceding night but battle fatigue had already begun to set in amongst the ‘rebels’. It was less intense than the night before. The extra 1,000 officers drafted in seemed to have succeeded in taking back control of the situation for the police. The Labour council leader Ted Knight described them as “an army of occupation”. There was only going to be one outcome.

“What is needed now is to build a completely new Brixton without any discrimination at all,” said the Brixton Neighbourhood Community Association who cited issues of frustration, unemployment, homelessness and alienation as factors that led to the disturbances.

The Scarman report into the riots concluded pretty much the same thing.

Comments Form